The American Journal

of Epidemiology in October 2016 published a report by Annah Wyss of the

National Institute of Environment Health Science and 20 government-funded

coauthors. It revealed that American men

had ZERO mouth cancers associated with dipping or chewing tobacco (Odds Ratio,

OR = 0.9), while women, who mainly use powdered dry snuff, had a 9-fold

elevated risk (here).

After trying for several months to correspond with the

authors, I wrote to the journal editor. My

letter was accepted, and the authors were invited to reply. The journal published both items on August 4

(here).

Here is my letter.

Because the references are important, I provide links to the sources.

“In the article… Wyss et al. omit key information that would likely yield critical insights about their most important result.“Wyss et al. reported that ever use of snuff among never cigarette smokers was associated with head and neck cancer (OR = 1.71, [95% Confidence Interval] CI: 1.08, 2.70), based on 44 exposed cases and 62 exposed controls. The OR among women ever snuff users (8.89, CI: 3.59, 22.0, based on 20 exposed cases and 12 controls) was an order of magnitude higher than that in men (0.86, CI: 0.49, 1.51, based on 24 exposed cases and 50 controls).“The striking difference between women and men reflects completely different snuff exposures. It is widely known that in the southern U.S. women primarily use powdered dry snuff, whereas men throughout the U.S. use moist snuff. Powdered dry snuff use is associated with excess oral cancer risk in four previous studies (Reference 2), all of which were cited by Wyss (3, 4, 5, 6). In contrast, moist snuff is associated with minimal to no risk in eight previous studies (2).“Wyss and colleagues are knowledgeable about the use of powdered dry snuff by women and its cancer risk; one was first author of a 1981 study reporting that “[t]he relative risk [for oral and pharyngeal cancer] associated with snuff dipping among white [women] nonsmokers [in North Carolina] was 4.2 (95 per cent confidence limits, 2.6 to 6.7).” (4) Subjects in that study had exclusively used powdered dry snuff.“Wyss et al. used pooled data from 11 US case-control studies located throughout the U.S. They have information to confirm that the 20 female [powdered dry] snuff users with cancer were from study sites in the Southern U.S., whereas the 24 male [moist] snuff users were from more diverse locations. This information is not available from the 12 publications cited by Wyss et al. as data sources. Six publications had insufficient information about exposed and unexposed cases and controls (i.e. no specificity with respect to smokeless tobacco type, gender, and/or smoking), three reported no results related to any smokeless tobacco product and three did not mention smokeless tobacco at all.“Wyss et al. should provide in tabular form the number of exposed and unexposed cases and controls separately for never smoking men and women from each of the 11 source studies. This information is routinely provided in publications of pooled analyses, and it is available in the existing data and results files.”

In their response, Dr. Wyss and her coauthors provided

additional results, per my request. While

they confirmed no risks among men who dip, their conclusion about women was

grossly inaccurate: “Snuff use was strongly associated with elevated [head and

neck cancer] risk in both Southern women…and non-Southern women.”

In Southern women, the risk was quite high (OR = 11.25) and

statistically significant, but with a wide 95% confidence interval (2.14 –

59.07), owing to the fact that the OR was based on only 26 cases. In non-Southern women, the OR was even higher,

at 15.91, but this was based on a mere 6 cases.

While statistically significant from a technical

perspective (CI = 1.20 – 211.43), the CI is so large and unstable that the estimate

is virtually meaningless.

Dr. Deborah Winn of the National Cancer Institute knows that

powdered dry snuff is the only smokeless product with mouth cancer risk (evidence

here,

here,

here

and here);

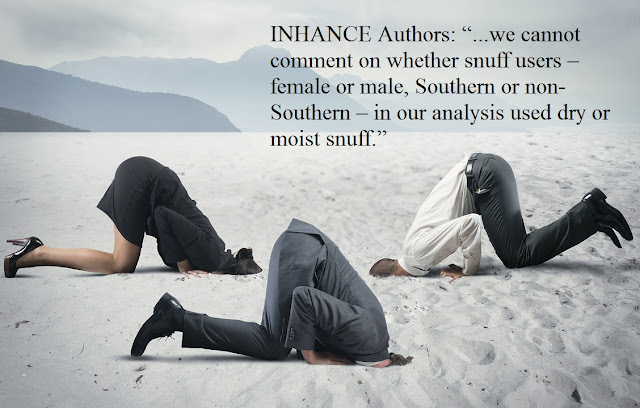

she published a study in 1981 that falsely implicated dip and chew. Even though Dr. Winn co-authored the new

report, the authors’ only comment on powdered dry snuff was, “we cannot comment

on whether snuff users – female or male, Southern or non-Southern – in our

analysis used dry or moist snuff.”

To be clear, numerous studies since 1981 have demonstrated

that the huge difference in mouth cancer risk between women and men is attributable

to powdered dry and moist snuff. Yet federally

funded researchers continue to misrepresent these established facts in order to

sustain the fiction that all smokeless products are hazardous.

No comments:

Post a Comment