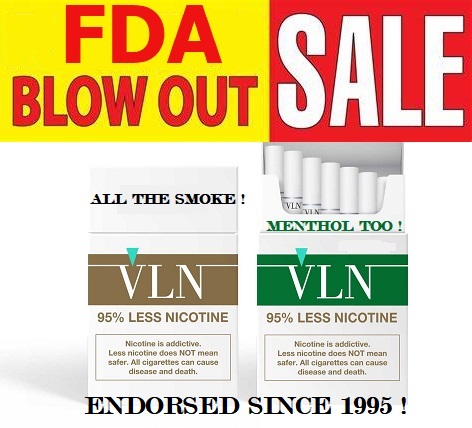

The Well News on January 25 published my commentary on the FDA’s recent regulatory blunder of approving a cigarette that provides all of the smoke but almost none of the nicotine of a traditional cigarette.

Upon its publication, I received a

number of critical emails suggesting that I had failed to properly research the

issue. In fact, those critics failed to

do their due diligence on me. To help

them, here is another analysis I published on the subject – back in 1995.

A group of tobacco reformers, led by the Food and Drug Administration Commissioner, has a new regulatory strategy: reduce the amount of nicotine in cigarettes. The theory is that the nicotine concentration of cigarettes will be too low to allow nicotine addiction to be established in new smokers. In the meantime the strategy is intended to serve as a (mandatory) national withdrawal program for the nation’s current smokers.

The FDA commissioner has collaborators in this regulatory quest at the highest levels of academia and government. Two well known experts on nicotine addiction, Dr. Neal Benowitz from the University of California at San Francisco and Dr. Jack Henningfield from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, wrote an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine essentially endorsing the fadeout plan. Although they admitted that “a threshold for nicotine addiction is a theoretical concept ...,” these researchers still postulated a safe concentration of nicotine in cigarettes that would prevent addiction in new smokers. To reach this level, the FDA would have to order a reduction in nicotine content from about eight milligrams per cigarette to about one-half of a milligram, representing a 94 percent reduction.

Although the fadeout idea has not been tested with regard to prevention, the plan has been studied for many years as a smoking cessation option. It is basically a drawn-out variation of a strategy called nicotine fading, in which the smoker’s exposure to nicotine is gradually reduced to very low levels. The concept was first introduced in 1979, and numerous trials, usually combining nicotine fading with other behavioral modifications, were conducted throughout the 1980’s.

In a recent review of 21 different quit-smoking strategies, nicotine fading came in with an unsurprising success rate — about 25 percent. Dr. Michael C. Fiore, director of the Center for Tobacco Research and Intervention at the University of Wisconsin, questioned the effectiveness of this strategy in helping current smokers quit. Of course if the FDA has its way, this program will not be optional. In other words, a large percentage of current smokers may not find this forced nicotine withdrawal a pleasant experience. What will they do?

As they did with low tar low nicotine cigarettes and those with filters, smokers will initially respond to the nicotine phase-out plan by smoking more often and more intensely. Benowitz and Henningfield acknowledged this problem in their editorial. They responded by saying that these smokers’ “short-term (ten-year) risk may be offset by the long-term benefit of a greater likelihood that they will quit smoking (as cigarettes become less satisfying) and by the enormous benefit of preventing nicotine addiction in future generations.” In other words, they are sorry if your risks increase for ten years because you can't quit, but maybe you'll quit anyway and besides, maybe your children won't get hooked.

Another drawback to the fadeout plan is its potential to spawn another huge illicit drug problem. The FDA commissioner commented that “even if we don’t ban cigarettes, we could create a black market by removing the nicotine too quickly.” He seems to believe that the problem is avoidable simply by reducing the nicotine slowly. He is undaunted: “We need to withdraw it at just the right pace, letting the addiction fade as we reduce the nicotine.”

There are other fundamental problems with the strategy. For example, setting a threshold level of nicotine exposure below which it is not addictive is an extremely speculative tactic. This would imply that there may be a “safe” level of consumption for all addictions including alcohol, cocaine, and heroin. A caffeine comparison serves us well here. Utilizing the same rationale concerning effect on body function (addictive potential) and intent (ability to manipulate levels), the FDA has ruled that caffeine is a food additive at concentrations up to 0.02 percent. This amounts to 72 milligrams of caffeine in a twelve-ounce soda. The FDA designates over-the-counter products containing caffeine (up to 200 milligrams per dose) as stimulants. Consistency is not a strong feature of the FDA’s caffeine policy, because a twelve-ounce serving of coffee can have as much as 400 milligrams of caffeine.

The important lesson from the caffeine analysis is that the FDA can draw on a precedent for every aspect of the nicotine fading strategy. The plan seems to be bolstered by an elegant scientific rationale, and it superficially appears to be a new and creative approach to the problem of nicotine addiction. However, that's where the real problem lies. Because antitobacco groups have passed judgement on nicotine addiction, they have focused all of their energy on eradicating tobacco. The nicotine fade is simply a thinly veiled disguise for tobacco prohibition.

That was my view, published 27 years ago in my clearly timeless book, For Smokers Only: How Smokeless Tobacco Can Save Your Life. Dr. David Kessler was FDA Commissioner at the time.

At the FDA, despite dramatic advances in tobacco science, virtually nothing has changed.

No comments:

Post a Comment