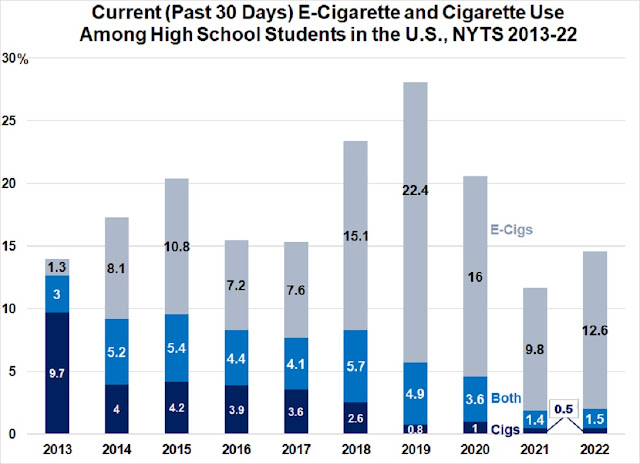

Reviewing CDC data from the 2022 National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS), I have confirmed the agency’s finding that 14.1% of high school students (2.15 million) reported current (past 30 day) e-cigarette use, an increase of 2.9%, or about 430,000 students. The survey also indicates that high school cigarette smoking was stable at 2%.

Yet, once again, the CDC’s data, and the agency’s spin on it, raises some critical concerns.

First, about 1.42 million vapers had used other tobacco products and devices, including cigarettes, cigars, pipes, hookahs, smokeless tobacco, nicotine pouches and/or heat-not-burn (HNB) products.

With respect to HNB, the NYTS has some strange data points. An estimated 319,000 high schoolers reported that they had ever used HNB, and 114,000 were current users in 2022. That is simply impossible. The only HNB ever sold in the U.S., Philip Morris International’s IQOS, was removed from the market in 2021, owing to a patent lawsuit. In addition, PMI implemented strict controls that made it highly unlikely for teens to have obtained these products. HNB ever and current usage might be explained by teens confusing those devices with vaping products. In fact, over three-quarters of high schoolers in NYTS who reported ever using HNBs also were ever users of e-cigarettes.

Of the 729,000 current “virgin” vapers who had never used another tobacco product, 495,000 vaped infrequently (19 days or fewer in the past month), while 234,000 vaped 20+ days. This means that only 1.5% of American high school students with no other tobacco use could conceivably be addicted to vaping nicotine. Although this is cause for concern, it is nowhere near a true “epidemic,” even though anti-tobacco activists use that term incessantly in collusion with the CDC.

As I have noted previously, high school vapers are not just using tobacco/nicotine. CDC and FDA vaping screeds routinely ignore high rates of marijuana vaping. The next chart shows that marijuana vaping has become even more popular; for example, a large majority of virgin high school vapers, regardless of frequency, have vaped marijuana.

Federal officials’ continued profession of moral outrage about nicotine use is entirely misplaced. They should instead focus on real high school epidemics, including:

39% who text/email while driving

30% who drink alcohol

20% who use marijuana

17% who ride with a driver who had been drinking

17% who considered suicide in the past year

16% who carry a weapon

14% who binge drink

13% who drive after marijuana use

Those teens are at real risk of injury and death.